In the New York Times today, we hear the story of Matthew Sprowal, a Harlem eight-year-old who “is bright but can be disruptive and easily distracted.” Through the city’s lottery system, Matthew won placement in a much-lauded charter school, only to be (apparently) forced out after his behavior problems came to light. Today, the boy’s mother says, he is thriving in a regular district school.

Matthews story illustrates a concern of many who follow education. Do charter schools owe their high test scores, graduation rates and other indicators to selectivity? While legally charters must accept any student, are they finding ways to avoid educating the most challenging children?

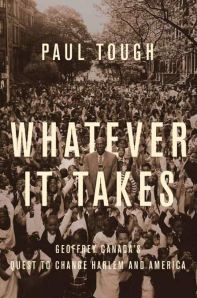

Meanwhile, over at the Times magazine, Paul Tough takes on the backlash against Diane Ravitch, who recently questioned the results that high-profile charters trumpet. Her op-ed in the Times drew scathing replies from many in the education reform movement, including Arne Duncan and the founder of Chicago’s Urban Prep, Tim King.

King acknowledged that just 17 percent of his 11th-grade students passed the statewide achievement test last year, while in the Chicago public schools as a whole, the comparable figure was 29 percent. … [He] wrote that Ravitch was comparing “apples to grapefruits” by holding the students at Urban Prep, who are almost all black males from low-income families, to the standards of “children from all across Chicago.”

Tough notes “the obvious: These are excuses. In fact, they are the very same excuses for failure that the education-reform movement was founded to oppose.”

Many of the schools that Ravitch and Tough mention are doing poorly, despite their high profiles. But instead of discussing how they can do better, their leaders lash out at critics. Tough responds:

To acknowledge this fact is not to say that reform is doomed; it is not blaming students or insulting teachers. It is merely reminding ourselves that the 83 percent of 11th-grade students at Urban Prep who didn’t pass the state exam, and the 85 percent of 9th-grade students at Bruce Randolph who didn’t pass the state writing test, deserve better.

This debate playing out in the pages of the Times and the Huffington Post may be the result of the rancorous climate in education today. With nearly every state struggling to dig itself out of a budget crisis, education funding is in short supply. (Free market philosophers might believe that competition for scarce resources is good for schools, but evidence points to the contrary.) School districts do not have the funds they need to succeed, and from this embattled position they see charter schools and education reformers as the enemy.

As they fight off attacks from traditional public schools, some charters find themselves struggling to live up to the promises the movement made in the beginning. By shedding problem students, by presenting their numbers in misleading ways, they hope to dodge criticism that could lead to the loss of their own precious funding. Rather than acknowledging where they need to improve, they, like many districts, crouch defensively.

I think Jim Manley, the superintendent of the struggling Sto-Rox School District, just outside Pittsburgh, put it well when he told me recently that he would like for his district to learn from charter schools, rather than fighting them.

“It’s hard to open up your arms to charter schools when we’re in competition,” he said. But, “I respect what they’re doing…. Let’s buddy up and see if we can learn together.”